In Jane Austen’s 1815 novel Emma, the character Mrs Elton is scathing about some recent acquaintances. “They came from Birmingham, which is not a place to promise much, you know, Mr Weston. One has no great hopes of Birmingham. I always say there is something direful in the sound.”

Her conversation felt like it was being repeated a few weeks ago, albeit on social media. It began with an article by Will Lloyd in The Times, which claimed Birmingham was “leading the nation in decline”. Typical of the reaction was one professional journalist, who pointed to English tourists going to Belfast and added: “can you imagine anyone having a city break in Birmingham?’ (In fact, according to VisitBritain, Birmingham is ahead of Leeds, Newcastle, Bath and Bristol in terms of visits for breaks, if you must know).

This might surprise some, and I’d argue that the reason for that surprise is also behind why Brum’s most struggling areas are taken as typical of the city in a way that they are not in other places. A ‘rough’ bit of Manchester or London is just that; an equivalent part of Birmingham is, well, just what you’d expect in that dump. Meanwhile, I was told just a few days ago that the ‘nice’ bits of Brum – Edgbaston and Harbone in this instance – were ‘not really Birmingham’.

The jump to these conclusions happens because Birmingham’s reputation has not been great for a very long time. Based on my own experiences, a lot of people, usually those who haven’t visited that much, think it’s ugly, boring, run-down and full of people with ridiculous accents. And that’s when they’re being polite.

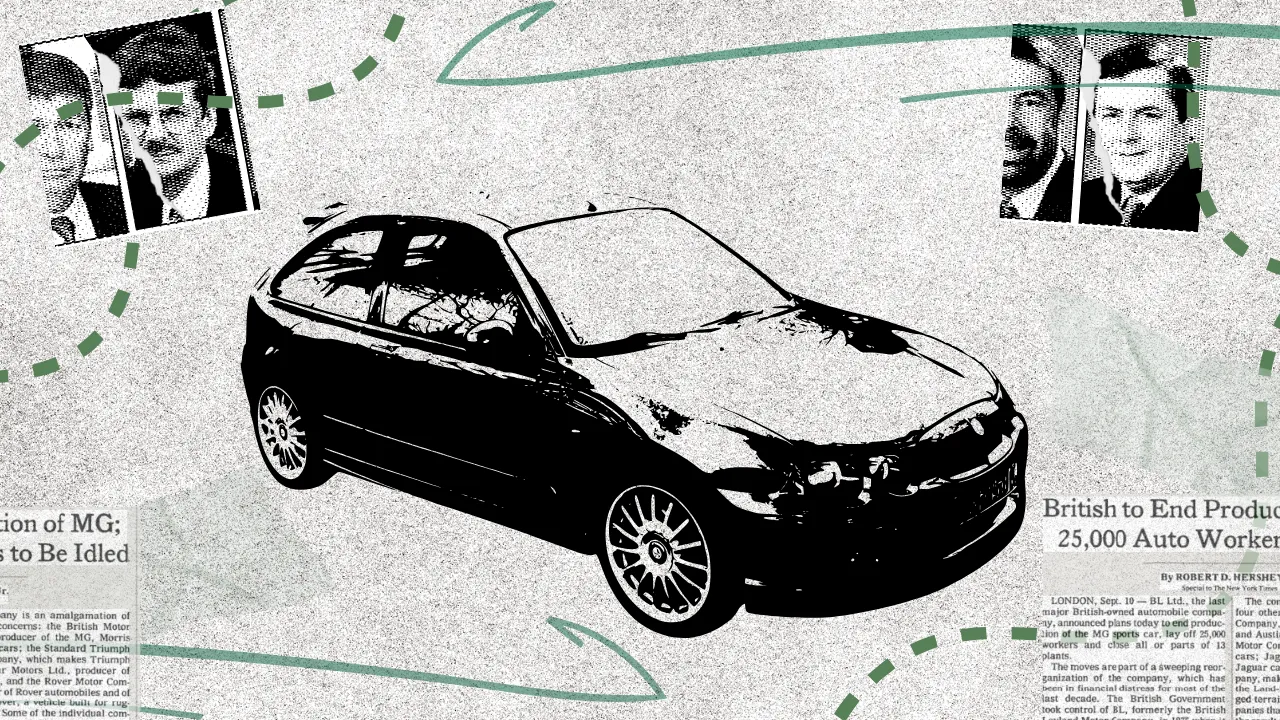

Blame it on Brummie indifference or self-deprecation, but even the city's long list of achievements is little known. I’ve been asked on more than one occasion ‘what has Birmingham given the world except baltis, concrete and terrible cars?’ Well, maybe they have a point. Besides the first cotton mills, the first steam engines, the first plastics, the first building societies, two of Britain’s major banks, the first technical schools, the first red brick university, the first municipal art schools and concert halls, the football league, major early advances in nuclear physics, the first patient-controlled pacemaker, heavy metal, fantasy fiction and perhaps the entirety of industrial civilisation, what exactly has Birmingham done for us?

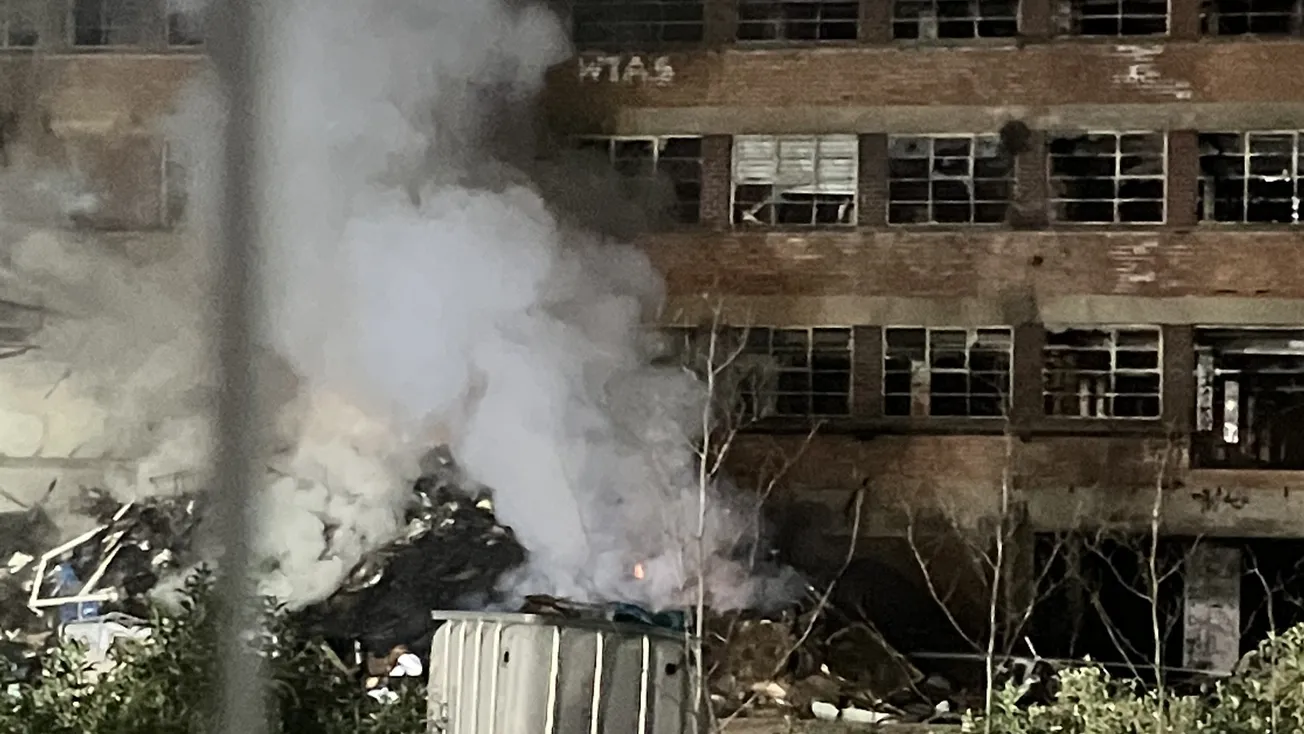

Part of the image is understandable. The city did make the worst town planning decisions in the country in the 1960s, with stiff competition. The best bits of Brum are spread out and hidden away; some other big cities have most of the stuff that’s worth visiting within a few minutes’ walk of the main station. We have New Street.

But the vitriol the city gets has always puzzled me. It’s understandable why it would be seen as lacking if your standard of city is York or Bath, Oxford or Cambridge. Even London. But why is it judged so poorly compared to the other inland industrial cities – Leeds, Manchester, Bradford, and Sheffield?

For me, it’s partly about geography, its straddling of both key transport links as well as the north/south divide that defines English life. But it's also about its history, and how its image has changed over time.

What’s more, as with Brum, all those cities have similar origins; small market towns, previously relatively obscure, that grew insanely fast in the late 18th and 19th centuries to become the largest cities outside London today. So when did things change?

Birmingham’s tendency to think of itself as being uniquely without history is odd, which I ascribe to it often comparing itself to the historic towns that surround it, rather than those obvious peers to the North. After all, Birmingham was larger earlier than the other industrial cities. By 1700, it was a town with as many as 20,000 inhabitants, compared to Manchester’s 15,000, Leeds’ 12,000, Sheffield’s 7,000 and Bradford’s 5,000.

And its history as an industrial centre goes even deeper than those peers. By the 1500s it was already known for its metalworking; William Camden described it as a town “swarming with inhabitants and echoing with the noise of anvils”. A century later, Celia Fiennes noted that it was “very black and smoky, and all full of workshops, for they are a people that work very hard” – a sentiment that would be repeatedly expressed for the next few centuries.

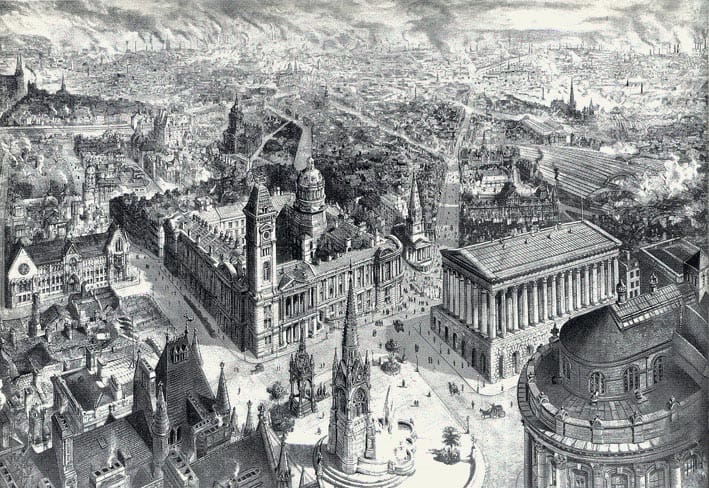

Interestingly, though, while its later Victorian image is sometimes fairly indistinguishable from the other major industrial cities, early writers were often positive about the city – perhaps reflecting the positivity of Georgians towards industry, progress and cities generally. By the 1700s, its status as a centre of industrial innovation and intellectual life more generally was beginning to be recognised. Samuel Johnson called Birmingham “a city of philosophers” (meaning science), while the Scottish clergyman Alexander Carlyle described “a place where invention and industry go hand in hand, and where men seem to breathe nothing but trade and manufacture."

This reputation only grew over the century. Johnson’s biographer Boswell describes “everything in a state of bustling prosperity”; while the travel writer Arthur Young referred to it as “one of the most prosperous and busy places in the kingdom.” This was, of course, the heyday of the “Midlands Enlightenment”, with Birmingham propelled to the forefront of European science and invention.

While plenty of visitors continued to comment on its smokiness and dirtiness, they were sometimes also struck by its new face. While the old town around Digbeth and the Bull Ring was still an ash-encrusted chaos of forges, workshops and old buildings, there was also a new town: a classically planned Georgian one built by large landowners such as the Newhall Estate. This was focussed on the new church of St Philips’ (“a beacon of newfound elegance, rising above the manufactories in noble contrast”) and can still be felt in some of the streets nearby. William Hutton, the city’s first historian, describes the old town, “irregular and confused”, giving way to the new, “spacious and elegant, where every rising edifice seems to exceed the last in beauty”.

So far, so good. But this was all to change. As the industrial revolution gathered pace, the city became more and more crowded, dirty and smoky. The fields around the new town become covered in mean hovels and back-to-back terraces; the gardens of many old houses were filled in with hovels and became the city’s notorious ‘courts’. Thomas de Quincey described the streets as “dark and gloomy as if they were deepened by the shade of perpetual smoke.” He added “I cannot divest myself of the impression of sadness and gloom pervading the atmosphere.”

If you think the Austen quote or the extract from De Quincey are harsh, consider what comments other cities were getting at the time. According to de Quincey’s friend Coleridge, Manchester was “continually overcast with smoke, its streets narrow and sordid, its houses without grace or elegance. Meanwhile, John Ruskin said that Sheffield was “a city of unmitigated ugliness, where everything is blackened and poisoned by industry”, while Leeds was “the ugliest and least attractive town in all England”, according to German traveller JH Kohl. I could go on.

Birmingham’s soot and grime, for a while, took a back seat compared to the “hell” of the more rapidly industrialising northern cities. By the mid-century, though, its reputation took a nosedive again. Despite the popular new town hall, built in 1834, it became evident that other cities were seeing more civic improvements and grand buildings. Birmingham was lagging behind, with and starting to get a reputation for being even more chaotic. Nathaniel Hawthorne called it “factories and workshops, with little to please the eye or soothe the spirit”, while to an 1851 writer in The Times it was a” labyrinth of industry, where the beauty of order has been sacrificed to the frenzy of production.”

This created the impetus for improvement, training and education that drove Joseph Chamberlain and the municipal gospel. This is not the place to list its achievements, but three decades after The Times’s harsh words, it wrote about “a triumph of municipal ambition, proving that Birmingham is not merely a place of factories but also of intellect and refinement.” A few years later, it was “the best governed city in the world”.

This, though, also created a problem for the city. While the northern towns were nurturing the Labour Party and Trade Unionism, Birmingham was nurturing the Liberal Caucus. For some writers, it lacked the working-class culture and solidarity of the north; its more skilled artisan base could sometimes be quite conservative.

This generalisation has always made Birmingham somewhat problematic for a certain type of left-intellectual writer who is not all that familiar with the complexities of its history. Its later embrace of protectionism creates a similar issue for commentators on the liberal right. For both sides of the political spectrum, there are plenty of reasons to be distrustful of what are presumed to be Birmingham’s instincts.

This wasn’t the only reason why its image began to diverge from other cities. Before the turn of the century, Birmingham was just another industrial town in the northern half of England. But the 20th century brought a whole new set of economic challenges for Britain. These were particularly felt in the North. Staple industries like shipbuilding and the Lancashire cotton industry fell upon hard times.

George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier, the classic document of this period, sometimes comes across as a 1930s version of the “poverty tourism” YouTube videos of today. “Sheffield could justly claim to be the ugliest town in the old world”, while “Manchester is the belly and guts of the nation”. JB Priestley was equally scathing during the same period “Between Manchester and Bolton the ugliness is so complete that it is almost exhilarating. It challenges you to live there”. To HV Morton, “The whole of Leeds should be scrapped and rebuilt.” At this point, Birmingham seems to be getting off lightly.

The north/south divide — once about industrialisation and modernity — became reclassified as one of poverty and lack of opportunity. The north became synonymous with unemployment; the question of what to do about it became a pressing national issue. There was a lot of establishment sympathy to this plight, which was sometimes seen as inflicted on it by Westminster – a feeling that would be strengthened by later events such as the Miners’ Strike. Birmingham, which remained prosperous (Orwell wrote that “between all the towns of the Midlands there stretches a villa-civilisation indistinguishable from that of the South”) was excluded from this sympathy from the start.

This may be connected to something Orwell notes in Wigan Pier: “There exists in England a curious cult of Northernness, a sort of Northern snobbishness.” He then points to a man of “advanced opinions” who, no doubt, would be horrified at the idea that an Englishman was more worthy than a foreigner – but had no problem suggesting that the residents of the north were somehow more noble or deserving.

I would argue the sentiment lingers on, that the problems of the North are seen as being those of government neglect, the problems of Birmingham more inherent and self-inflicted. Northern cities deserve the greatness denied by London; as one recent book insists, “The North will rise again.” Indeed, the past decade has seen a revival in the cult of the north, with a plethora of books, the IPPR North think tank, the Northern Powerhouse initiative and so on – institutions Birmingham is excluded from by history and geography, despite similar and sometimes more intense problems.

The 1920s and 1930s also saw a peak in the cult of the rural, particularly the unspoilt South Country and the Southern Midlands. Then Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin — a Worcestershire man — declared “England is the country; the country is England”, and he certainly wasn’t referring to the northern moors. Joseph Priestley, typical of the era, was horrified by West Midland industrialism, not blending in with the harsh landscape as in his native Yorkshire, but existing so close to Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden.

So, Birmingham was seen as lacking northern virtues, but also as an industrial impingement on the idealised, bucolic landscape of Warwickshire and Worcestershire. Visitors such as Priestley were horrified not so much by its squalor but by its brash mass affluence and modernity, its traffic-clogged one way streets, its new housing, cinemas, tudorbethan pubs and arterial roads. More so than in other cities, ordinary people were spreading out in the countryside with all their vulgarity, and the educated elite were not impressed.

The late 1890s and early 20th century sees the accent first being exaggerated on stage for comedic purposes. While the Birmingham MP Thomas Attwood had been mocked in Parliament for his speech, in the early 1800s, it was because it was provincial, not because it was specifically West Midland. But from the 1890s onwards we start to see music hall sketches such as The Brummagem Gent:

Londoner: “And where might you hail from, sir?”

Brummie: “Brummagem, good sah! An’ proud of it, oi am!”

Londoner: “Oh dear, do they all sound like that up there?”

Brummie: “No, some on ‘em spake proper bad.”

This continued post-war, with figures such as Beryl Reid’s “Marlene”, Benny from Crossroads and “boring Barry the brummie” from Auf Wiedersehen Pet (actually from the Black Country, but never mind).

This was the baggage that Birmingham had before it even entered the post-war period; after initially being admired for its affluence and energy, it soon became notorious for its ring roads and its concrete, its problems around race and immigration, and industrial strife in its car factories. Some of the criticism, particularly around Manzoni’s redevelopment, is understandable. Even if there was always far more to Birmingham than this, once cliches are embedded they are hard to shift.

Mrs Elton was, of course, a terrible snob who Austen was poking fun at. Modern day snobbery and blanket criticism are pushing on a door that has been open for over a century; perhaps they need to be shown that they are taking an easy and lazy option too.

Correction: The Jane Austen character who bashes Birmingham is Mrs Elton, not Mrs Weston, as originally stated. This has been corrected.

Comments