I’d heard the rumours but they didn’t seem real. No one goes out anymore, I’d been told. Young people just aren’t interested. They don’t dance. They don’t even really talk. The battery chicken youth have killed the club, apparently, too busy cooped up inside being members of strange online cults like Inceldom or Sobriety. The Big Night Out was long dead, buried in an unmarked grave next to skinny jeans and Being Able to Afford Your Own House (without being a member of the landed gentry); upon which a few washed up clubbers have laid a shrine of empty Smirnoff Ice bottles.

Of course, I refused to believe it. I’d become hooked on going out in the late noughties, drawn in by the permissibility, community and leftfield sonic passageways dotted through Digbeth, Jewellery Quarter, Moseley and Kings Heath. I might have turned up too late for Birmingham’s true golden days (the eighties and nineties steal this crown, where clubbers could choose between Que Club, Powerhouse, or even the Rag Market — or hit them all in one night) but I loved it anyway.

I loved the rituals that existed — the build up, the smoking area encounters, the pre-club penguin huddle because no one had enough layers on. Surely this stuff was too deeply embedded to be lost? I loved the fact Birmingham had venues that put it on the map. People you’d meet from all over the country would recognise the names. “Oh you’re from Birmingham, they might say. Have you been to Gatecrasher? Have you been to Rainbow Venues? A city needs these places. Because what’s the alternative? “Oh you’re from Birmingham. Have you seen those exciting new builds they’re knocking up over in Digbeth? Cracking ROI if you get in early enough.”

It’s easy to be dismissive of clubbing, if you reduce it to its bass metals; drinking, music, throwing up in a bin as the sun rises. But it was more than that. One of my own club night high water marks was a night spent dancing with a loved one in a single-room space: a conversation between two bodies in which the background cast of clubbers melted away.

So last weekend, turning 34, I decided to Go Out. A world-famous DJ was playing at XOYO, the sister venue to the DJ Mag Top 100 club of the same name in London. I’ll freely admit I’m past my own clubbing peak but, on the night, XOYO wasn’t doing much better, less than a third full. If I’d paid attention, signs were there: 24 hours before, promoters were desperately offering up free tickets to anyone who would take them. As it happened, the harbingers were right.

And while it’s obviously not just Birmingham, it is apparently especially Birmingham. Night Time Industries Association (NTIA) statistics show a 32.7% dropoff in nightclub activity across the country, as well as a big decline in nightclub spending since 2020; even Berlin, the so-perceived clubbing mecca, is struggling. But in Birmingham the numbers are even more unfortunate, a 38.5% decline over the same period; 177 night-time businesses lost between 2020 and 2023.

Figuring out why clubbing is in decline is a vexed question (not least for financial reasons —- according to 2023 NTIA data, the industry employs at least 60,000 people and has a £1457.3m benefit to the economy). You’ll have heard the arguments many times before; the rise of sobriety and wellness culture in young people, dating apps, the pandemic, the fact that no one has any money. These are the main ones, although there are more niche ones too. Tom, a local DJ who has been clubbing in Birmingham since the early 2010s, throws in one such suggestion: “Ketamine being the drug choice du jour since 2016 has subdued crowds,” he says. “It makes it harder to build a relationship between fans and promoters.” This isn’t the late eighties ecstasy boom after all.

Of course, these factors will play out in Birmingham but does the second city have characteristics that are specifically driving a more vertiginous decline in clubbing? Surely we don’t just have a particular hankering for horse tranquilisers. One theory is quite simple: while many in the country are hard up, in Birmingham it’s that much worse. For Tom, it’s this suppressed cash in pocket which then hardly goes far on a night out, especially when clubbers have to rely on taxis because of Birmingham’s sprawl and patchy transport. “Birmingham is the worst of all worlds: parochial transport links and gentrified nightlife prices,” he says.

For Poppy Ringrose, DJ and co-founder of Sigil Radio, an incubator for local DJ and musical talent, this means clubbers are less likely to be impulsive and try a night out resulting in many promoters, hardly breaking even as it is, not being able to afford the headliners or creative risks that might pull in a crowd. It’s a vicious cycle. “It all results in fewer people going out”.

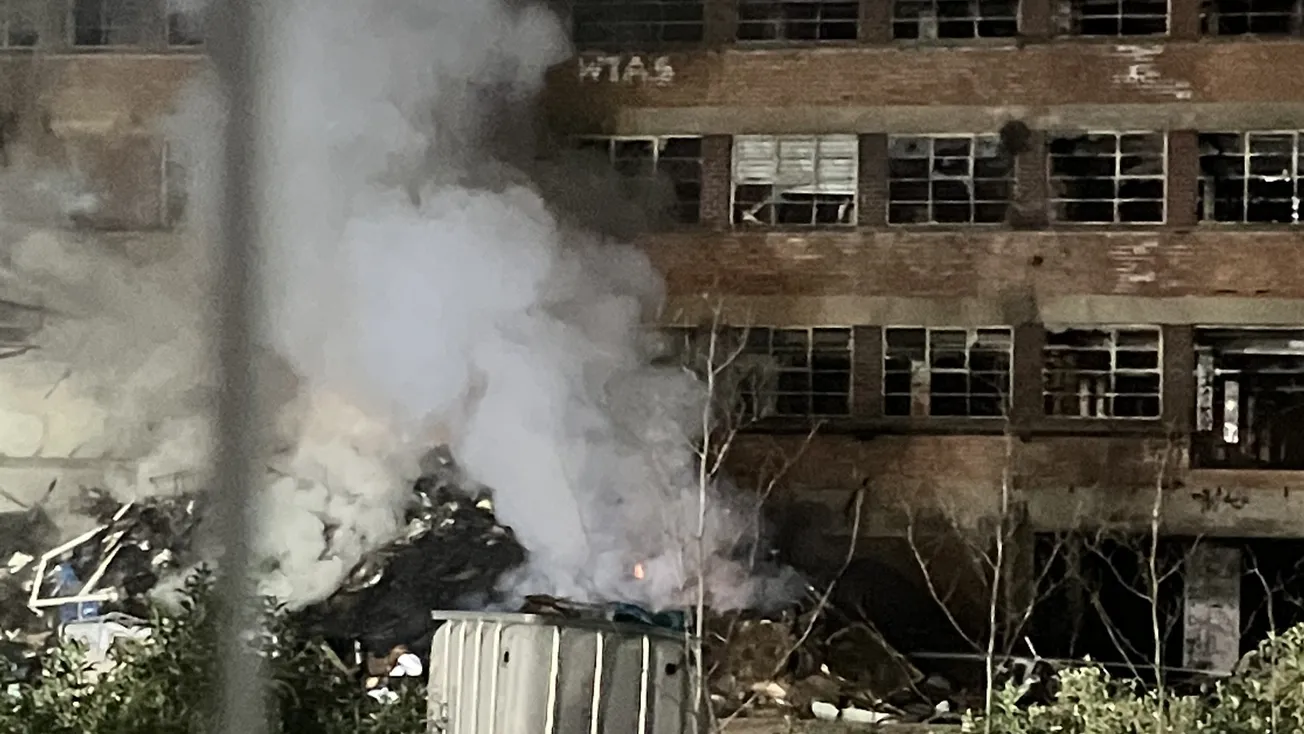

With high-rise living developments springing up in traditional clubbing areas such as Digbeth and Broad Street, Dr Matt Grimes, senior lecturer in music industries at Birmingham City University, says gentrification is also an issue. He describes one club opening recently, cutting deals with younger promoters in order to reinvigorate the grassroots, which had to shut down rapidly due to a noise complaint. “Ironic as [the complaint] was from the type of business that would benefit from having a club nearby,” he says. (He’s hardly the only one to worry about this — a spate of fitful sleepers popping up in the Gay Quarter led to tensions a few years ago).

Lyle Bignon, nighttime ambassador for Birmingham, argues that such incidents reflect the current planning, licensing and cultural models in the city, which fail the nightclub sector. “Officially recognising our late-night economy and clubbing communities and treating key buildings as protected cultural assets in the same way as daytime retail and concert halls could act as a real sign of confidence in the sector,” he says.

There’s also a feeling from some in the sector that, while deeply tragic, events such as the Rainbow Venues drug deaths in the 2010s and the fatal 2022 Crane nightclub stab, are used as opportunities to suppress the sector. But there are real safeguarding issues. Lily Harris, a 22-year-old student says she used to love clubbing but “it’s started to feel unsafe”. She says she’s been touched nonconsensually in clubs. “I have noticed an influx of people… who just walk around the place trying to scout out any women,” she adds.

Staring down the barrel of this laundry list of reasons clubbing in Birmingham isn’t working, perhaps it’s little wonder that some at the Combined Authority are said to favour simply focusing on what the city is doing well: food. But here’s the thing, Birmingham is good at clubbing too. George, another local DJ and promoter, is sure of this (even if it’s suppressed at the moment). Indeed, he says that the city’s racial and class diversity means that it supports a variety of sounds other cities couldn’t, and there is a constant revival of grassroots nights that might survive for a year or so and then stop.

“We have bhangra, amapiano, afrobeats,” he says. “Promoters have to understand this, bass music might do well in London but here we have different sounds.” While he admits this might mean a sparser audience, not least because promoters can end up attempting to appeal to the same small audiences, it does mean success might need a different metric in Birmingham. It’s hardly the same “gentrified, white” scene that might exist elsewhere.

There are certainly those attempting to keep it alive. A grassroots network of promoters and DJs support peers’ nights via WhatsApp communities and social media. DIY clubs like Pan Pan, the short-lived RMBL, nights at the Dark Horse, Centrala and the nationally acclaimed Hare & Hounds and XOYO support smaller, alternative club nights. That said, Grimes asks what if we don’t need the club at all for clubbing to occur. “What if [young people] are getting decks at house parties, affordably, not to make money, but to make culture,” he says, adding this, in its own way, speaks to the do-it-yourself energy of the Acid House era. I wonder if this idea might be extended. Illegal rave on the Smithfield site anyone? Perhaps not. “It’s difficult now, you’d lose all your equipment,” laughs Grimes, noting the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

Last week, dancing in a mostly empty XOYO, feeling the sort of awkwardness unique to mostly empty clubs, one thing was very clear: if clubbing, dancing and raving are to continue in Birmingham, they will have to evolve in something different from what people like myself are nostalgic for: our own clubbing past. Even those within the industry admit it might have to change, that clubbing as many are worried about, has already been and gone, that promoting practices might be outdated, funding models ripe for evolution.

But maybe that’s also an opportunity. It might mean experimenting with differentiated support for the sector — surely Bristol’s proposed music venue levy (adding a 1% fee to tickets sold by larger venues to reinvest in the grassroots), Camden’s consultation on extended licensing laws (self explanatory enough — keeping pubs open later) or London’s After Dark strategy might be replicated in Birmingham? Mind, they’ll need to move quickly. And the recent news, broken in The Dispatch, that one Night Time Economy advisor, restaurateur Alex Claridge, left his post after being left in the dark for months as to whether it was being kept on, isn’t the best start.

Luckily, us Birmingham lot being stubborn and used to being up against it, means there’s a lot of grit. As Tom says, the promoters that exist now work hard and, critically, have a ‘just get on with it’ attitude. “Luckily there's also lots of stubbornness and a very Brummie hard-headed approach,” he says. Ringrose, for her part, believes that a lack of a helping hand means there’s a chance to rebuild the scene in a way that speaks to the character of now. Indeed, she sees inspiration from within Birmingham itself. “Look at the grime scene in Birmingham, they never see funding, they do it for themselves,” she says. “Good stuff is born out of struggle.”

Comments