From the tiny particles found in British rivers and streams, to the ‘trash vortex’ in the middle of the Pacific, it’s fair to say that plastic doesn’t have a great image. It has become a symbol of humanity’s mindless destruction of the environment, although it has also made a huge contribution to human well-being, providing new materials for construction, machinery and clothing. Modern food distribution, which we take for granted, would be very difficult without it.

Plastic, for good or bad, is everywhere. But few people know that the first synthetic plastic was invented in Birmingham. All that pollution — and usefulness — can be traced back to a man born in Suffolk Street in 1813: Alexander Parkes. The plastic he created would not only underpin the development of the more sophisticated plastics we use today; it would also, under a different name, drive the golden age of film.

Parkes seems to have come from a family of experimenters and tinkerers; his great-uncle Samuel Harrison was apparently the inventor of the modern split keyring. Initially apprenticed to a brass founder, Parkes began to make his mark in the world as an employee of the Elkington brothers. The Elkingtons had invented — and patented — an electroplating process which allowed a thin layer of metal, in their case silver, to be deposited on a wrought object with an electric current.

Elkington & Co’s skill in silverware, as well as in silver plate, propelled it to worldwide fame. Its products were a central part of the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, celebrated for having made both the Wimbledon Ladies’ Singles trophy and the cutlery on the Titanic. Its works are exhibited today at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Elkington’s original factory still partly survives on Newhall Street, having been the home of the Birmingham Science Museum between 1951 and 1997. (Much of the once-extensive facility was demolished in the 1960s.)

Parkes’ restless experimentation began here, where he was granted patents for improving some of Elkington’s electroplating methods so they could be applied to delicate objects such as flowers. But his scope extended far beyond their specialisms; his other patents included phosphor-bronze, the cold-cure process for vulcanising rubber, various new methods for tube manufacturing, and the ‘Parkes Process’ for de-silvering lead. During his life, he registered an impressive 66 patents.

His real breakthrough came in 1856, with his experiments in applying nitric acid to cellulose derived from plants. The product of this research could be dissolved in alcohol, moulded into any shape, and then hardened when heated. The end result was something that looked a bit like ivory. This was Parkesine, the first synthetic plastic.

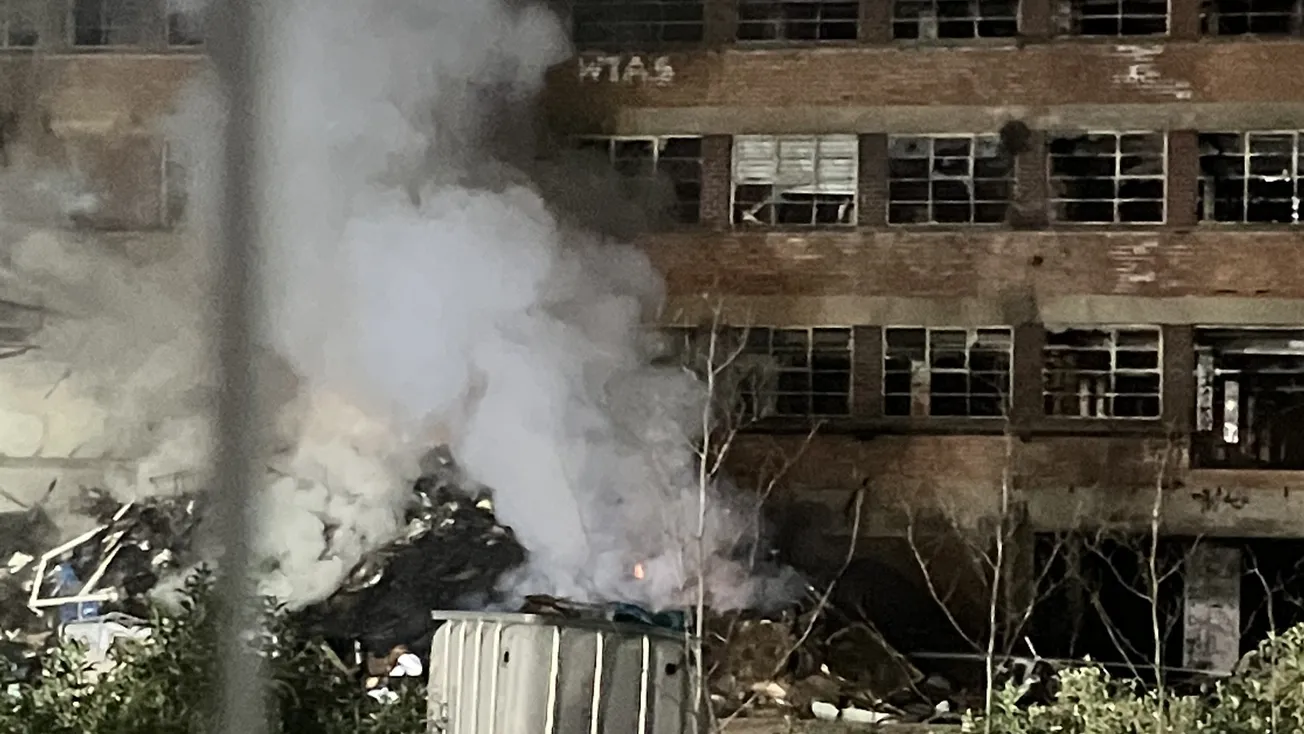

Four years later, Parkes set up the Parkesine Company in Hackney Wick, London, with a view to mass production. It never caught on, at least not in the way Parkes intended. It was highly flammable and prone to cracking. Two years later, the factory closed. This seems to have ended Parkes’ commercial aspirations; he retired to Dulwich in South London, where he died in 1890.

However, Parkes’ associate Daniel Spill was determined to make Parkesine a commercial success. Taking over what was left of the company, he renamed both it and the (now slightly improved) substance Xylonite. He eventually had success with the British Xylonite Company, employing more than 1,000 people and eventually becoming BX Plastics, which continued production until the 1970s.

Parkes is a very recognisable Birmingham figure; the solitary innovator, ploughing his own furrow furiously, only for others to benefit commercially in the long term.

Parkesine’s story does not end there, though. In the United States, New York-based John Wesley Hyatt had been experimenting with the substance, adding the camphor that Spill had used for Xylonite. He named the results celluloid and set up a production facility in Newark, New Jersey. It was used in place of ivory in many everyday objects, from billiard balls to fountain pens, but its most celebrated application was in photographic and cinematic film. It took some time to thinly slice what was still effectively Parkesine, but by 1889, the Kodak Company had patented the most successful attempt.

Spill was not one to take this piracy lying down. His was a common story; much early American industrialisation was based on the use of British inventions and innovations, sometimes gained through commercial spies. He brought several legal cases against Hyatt, and eventually the judge decided that neither he nor Spill were the originators, but that Alexander Parkes was the genuine inventor of celluloid, the material that drove the golden age of Hollywood.

In an 1887 letter, Parkes wrote: “In answer to the American inquiry, who invented Celluloid?… I do wish the World to know who the inventor really was, for it is a poor reward after all I have done to be denied the merit of the invention.” The ruling didn’t help him — both Hyatt and Spill were permitted to continue manufacturing, with no financial benefit to Parkes.

Birmingham’s contribution to film doesn’t end with Parkes and celluloid, however. In the early 20th century, the city produced four people — all members of its small, but longstanding and influential Jewish community — who would, between them, establish so much of the British cinema industry.

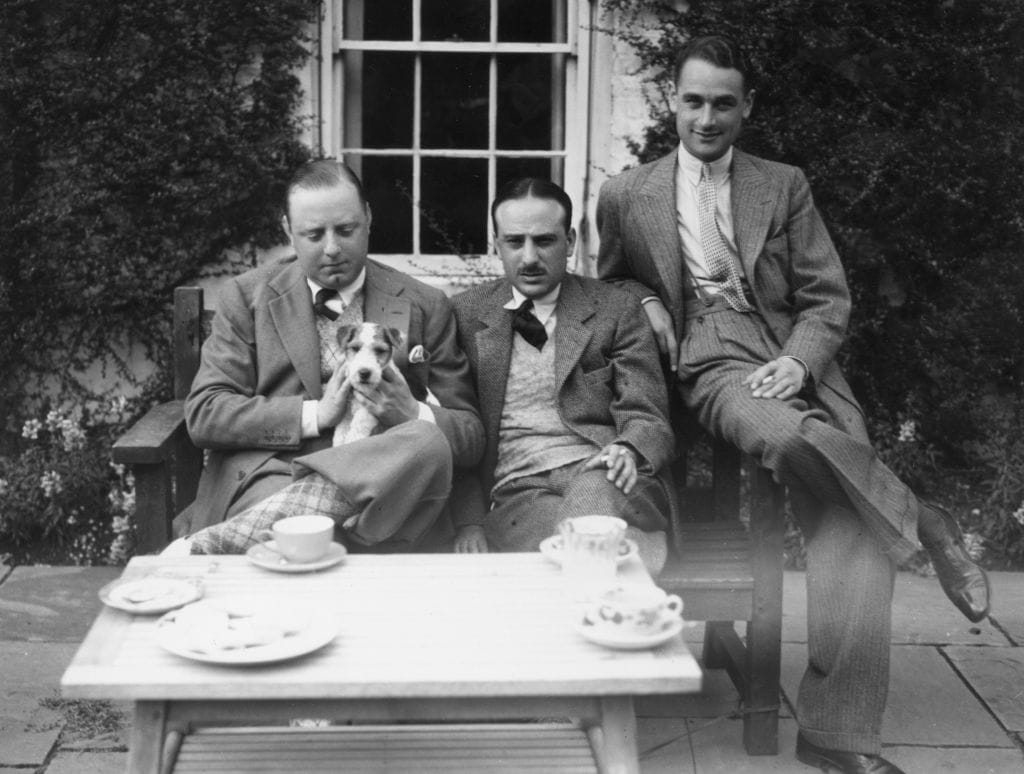

Oscar Deutsch, Michael Balcon and Victor Saville all grew up in and around the Balsall Heath/Edgbaston fringes. Deutsch was the son of a Hungarian émigré scrap-metal merchant; Balcon was brought up by a single mother after his Latvian-born father decided he ‘preferred to travel’; while Saville’s Polish-born father was a fine-art dealer. Despite going to different schools, they appear to have been friends as adolescents.

Saville had been discharged from army service in 1916 with serious injuries; his first job was a film salesman; he appears to have been the link with Sol Levy, an older Jewish entrepreneur who would be the inspiration and guide for the wider group. As well as acting as a film distributor, Levy built the Scala on what is now Smallbrook Queensway (demolished in the 1960s) and took over the still-extant Futurist on John Bright Street, the first cinema in Birmingham to show ‘talkies’.

Balcon’s poor eyesight had excused him from military service; he was working at the Dunlop plant at Aston Cross. Deutsch, meanwhile, was working in his father’s scrap metal business. In 1921, after Saville’s experience of working in London for Pathé newsreels, the three of them set up a new distribution company – which failed.

They apparently used the remaining money to bet on several football matches – and won – and founded Victory Motion Pictures with the proceeds. Balcon and Saville’s first film, Woman to Woman, was released in 1923. Based on a play, it was a commercial success (it also featured a young Alfred Hitchcock in assistant directorial duties). The pair would remake the film as a talkie six years later.

Saville went on to become one of Britain’s most successful directors and producers, serving as one or the other on 75 films over almost five decades on both sides of the Atlantic. The British Film Institute praises his films for their sympathetic treatment of women and their honest depiction of the British class system. He was once hauled in front of the U.S. Senate for producing anti-Nazi films for MGM, which also got the company banned in Germany by Goebbels. The Senate demanded his deportation, but he was saved by the outbreak of war after Pearl Harbour and continued to work for the studios for several years.

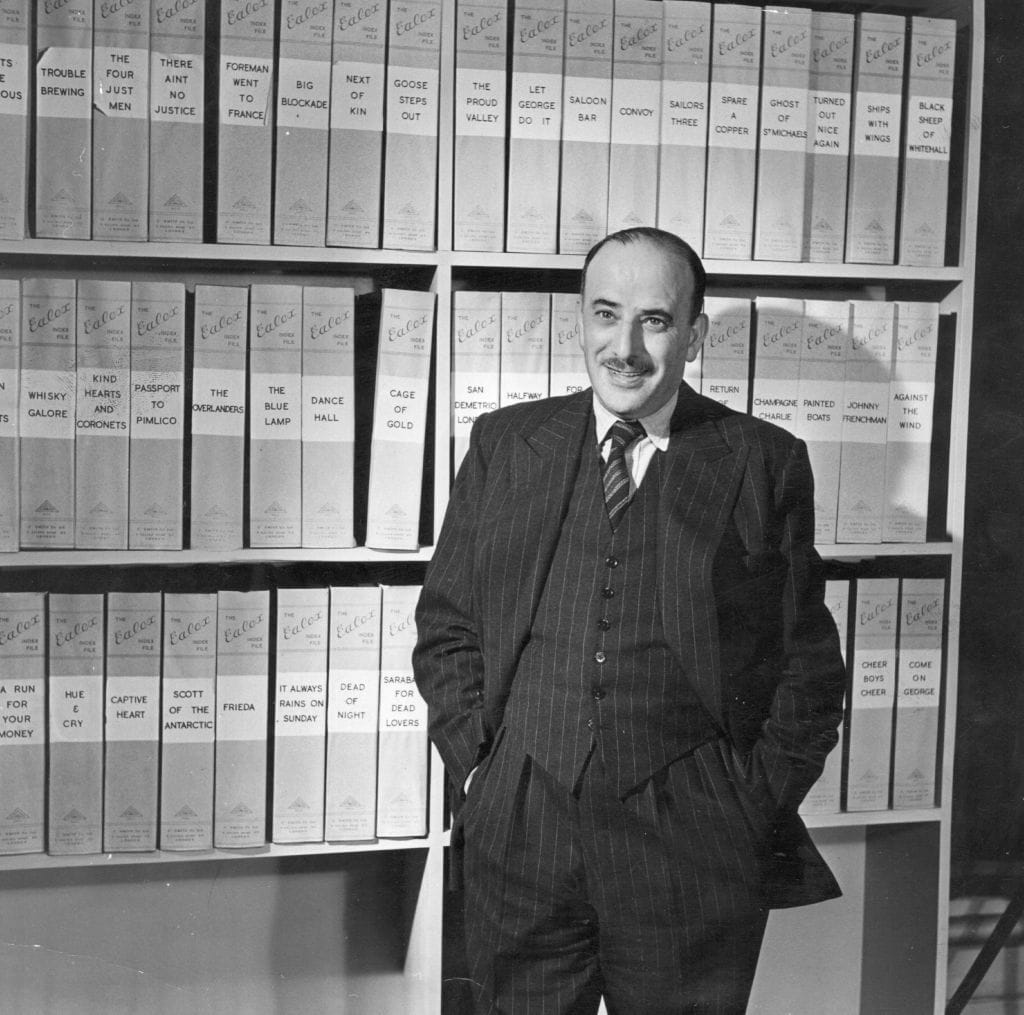

Balcon, meanwhile, set up Gainsborough Pictures, and later became director of production for Gaumont-British — overseeing the first film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. But his real impact came after the war, where as head of Ealing Studios he would oversee many Ealing Comedies (such as The Ladykillers and The Lavender Hill Mob) as well as a film called The Blue Lamp.

he main character in this, a policeman, was named George Dixon after the Birmingham MP and councillor who gave his name to Balcon’s school. Its spin off series, Dixon of Dock Green, was one of the most popular TV programmes of the postwar period.

Balcon, meanwhile, became one of the greatest supporters of the British New Wave, the string of realistic, kitchen-sink dramas produced in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The company he founded after the collapse of Ealing Studios, Bryanston Films, would release both A Taste of Honey and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, as well as a number of other classics.

Deutsch had a very different trajectory. He began by leasing cinemas around the Midlands before setting up his own Picture House cinema in Dudley. In 1930, he opened a new cinema in Perry Barr — the building still stands today — under the brand name he had devised. It was the old Greek word for amphitheatre and had been used for cinemas elsewhere in Europe; it also handily spelled “Oscar Deutsch Entertains Our Nation”. The first Odeon was in business.

Within 10 years, there were almost 250 Odeons around the country, and the name had become a general word for cinema. They tended to be more upmarket than other chains and were credited with bringing more middle-class patrons into the cinemagoing audience. Deutsch was also excited by modern architecture and the adventurous look and feel of the cinemas was masterminded by Handsworth-born, School of Art-trained architect Harry Weedon.

According to one critic, Weedon’s art deco designs “taught Britain to love modern architecture”. One of the best early examples survives in Kingstanding — what is now the Mecca bingo hall — but his most prominent work is the flagship Odeon in Leicester Square in London. Not only does it still function as a cinema, it is the venue for many red carpet film premieres: a piece of Birmingham in the heart of the West End.

He was also responsible for the motor plants at Longbridge and Cowley as well as the Typhoo Tea factory in Digbeth, which will become the new BBC Midlands HQ in 2026.

Despite the national success of his cinemas, Deutsch continued to live in the city — at Augustus Road, Edgbaston — and was president of Singer’s Hill Synagogue. In 1941, he was seriously injured when a bomb fell on his house. He died of cancer in the same year aged only 48.

Ian Francis, director of Birmingham-based Flatpack Projects, a charity that runs moving-image events across the Midlands, including the eponymous festival, is in no doubt about the importance of the trio. “It’s pretty amazing that these three friends grew up within a few hundred yards of one another and then went on to shape the British film industry in very different ways. Your career options as a young Jewish man were quite limited at the time, and I think that’s partly how they ended up in entertainment. They were also inspired by the example of local cinema entrepreneur Sol Levy.”

But Levy and Deutsch were not the only cinema moguls to hail from our city. Joseph Cohen was born in Ladywood. After training as a solicitor, he set up a partnership with a local cinema manager and began operating the Oxford and Tatler cinemas in the city centre. He was also an innovator, introducing news clips to Brummie audiences and pioneering continental cinema at the Tatler on Station Street and the Cinephone on Bristol Street. Under his Jacey company name, he expanded to other cities, and by the 1950s he owned or operated 50 cinemas nationwide. His two great contributions in Birmingham were the impressive Pavilion Cinemas in Wylde Green and Stirchley, now both demolished.

The stories of Parkes and cinema show, once again, the extent to which Birmingham shaped modern Britain and in some cases the world. But the city’s contributions to plastics, celluloid and cinematic history — as well as the role of its once-influential, now much diminished Jewish community — are barely visible, little known and rarely celebrated.

Take the cinema Cohen operated as the Tatler: originally called the Electric, it is the oldest in the city and later went back to its original name. Until the lease set up by Cohen expired in 2024, it was also the oldest operating cinema in Britain. It was refused listing by Historic England just a week ago.

At least Alexander Parkes, the man who invented the celluloid on which all those Odeons and Jaceys depended — until its notorious flammability saw it replaced by Kodak safety film in the 1950s — got a blue plaque, or rather three: one on the old Science Museum, one on the old Parkesine works in Hackney, and another in his later home in Dulwich.

Comments