“That’s Chuck Berry at the Hippodrome, that’s Nina Simone in her dressing room at the Town Hall, and that’s The Rolling Stones at ATV Studios in Aston,” says local music mogul, and Black Sabbath’s first manager, Jim Simpson. I’m flicking through a hardback book of mostly black and white photographs taken by him in the 1960s. Simpson’s office is an Aladdin’s cave of music history: VHS gig recordings are piled from floor to ceiling, boxes store thousands of newspaper clippings and opening the cabinets reveals an archive of original gig posters and flyers, going back more than 50 years. Simpson has kept records of everything, and it’s all hidden in plain sight in his professional digs on Broad Street.

At 87 years-old, Simpson has had a busy life. His office, the headquarters of Big Bear Music, reflects this. Under the Big Bear umbrella sits the likes of Big Bear Records — the oldest independent British record label, established in 1968 —, and Europe’s biggest free jazz party, Birmingham Jazz and Blues Festival, which Big Bear has organised since 1985. Last year, Simpson was honoured with the Lifetime Achievement gong at the annual Birmingham Awards, a celebration that recognises “standard bearers of success in Birmingham”. The city owes much to Simpson — but arguably, his greatest gift to the world is Birmingham’s loudest export: heavy metal.

“It was always about the blues for me,” Simpson says, excitement in his voice as he rolls off the names of American blues musicians he once brought to Birmingham, like Blind Gary Davis, Lightnin’ Slim and Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup.The latter wrote three of Elvis Presley’s first five hits, including ‘That’s All Right’.

“I was a fan of blues music from an early age and that prompted me to pick up a trumpet and play in bands myself,” Simpson continues. “In the mid-1960s I was in a band called Locomotive with John Bonham, who left to drum for Led Zeppelin. I said they’d never make it with a daft name like that. What do I know?”

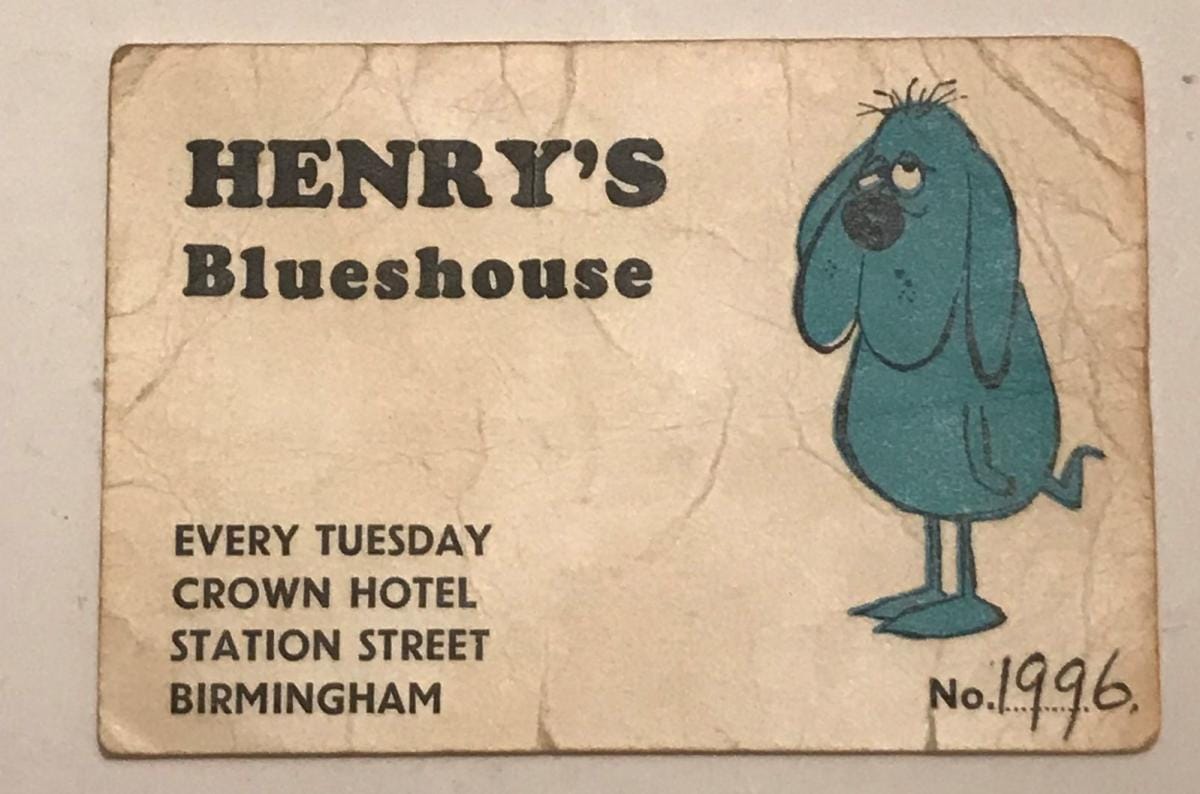

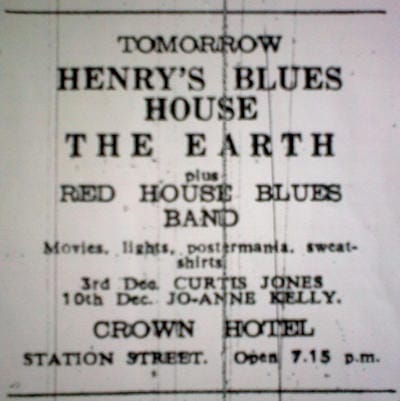

In 1968, Simpson also departed Locomotive to pursue a career as a music manager and promoter. Every Tuesday he would rent a small room above The Crown pub on Station Street, opposite New Street Station, and book bands for his live clubnight ‘Henry’s Blueshouse; (named after his neighbour’s “rather handsome Afghan hound”). It was in the confines of The Crown’s cramped upstairs that Simpson first encountered John Michael Osbourne and his mates.

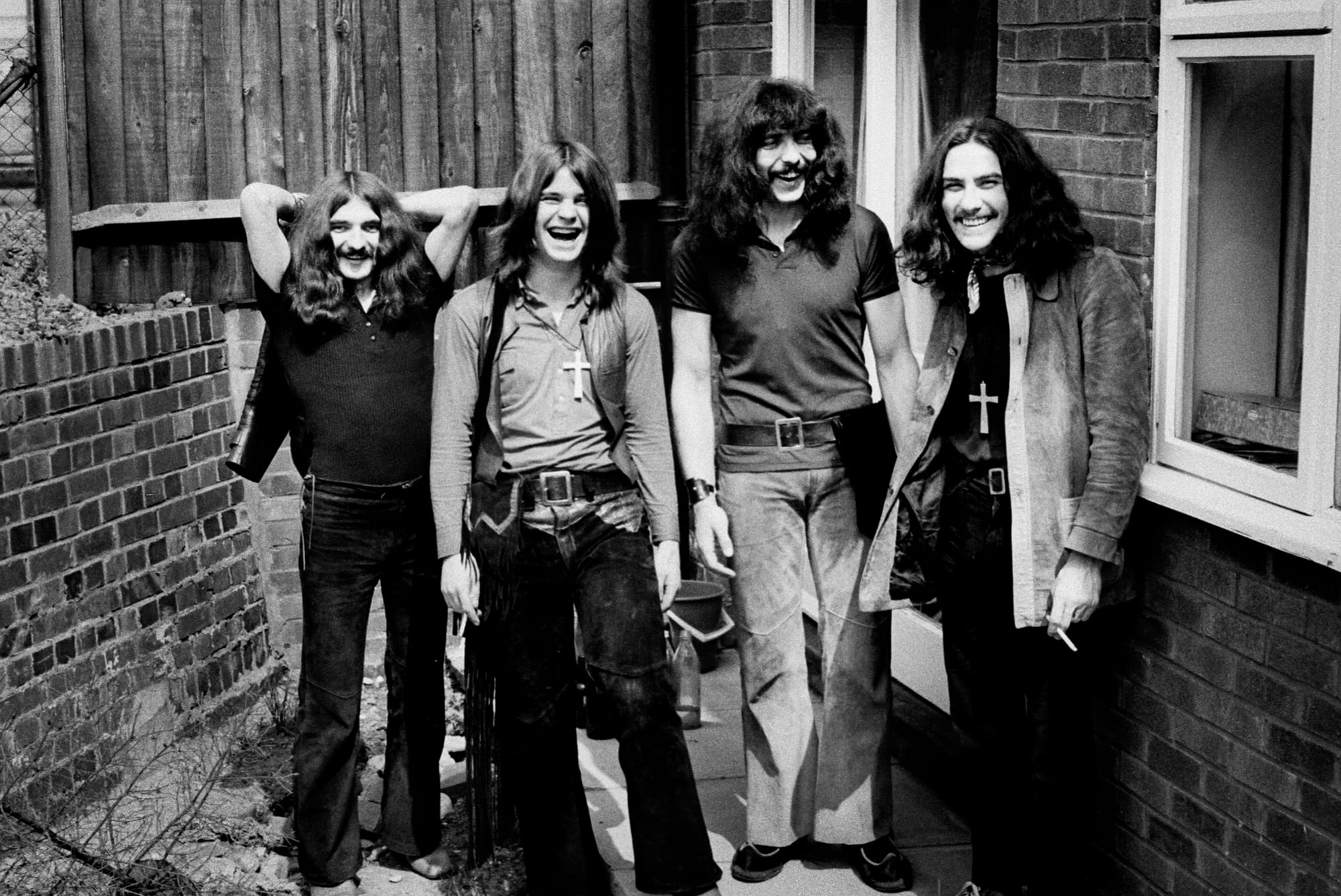

“Early membership records for Henry’s Blueshouse in 1968 show a John Michael Osbourne (Ozzy) and an Anthony James Iommi (Tony) as members,” says Simpson. Membership cost the boys a modest sum of one shilling a year. The duo were regulars. “They seemed like nice kids,” Simpson remembers. “They told me they were from Aston, and that they were in a blues band called Earth with their two other friends, Terence Butler (Geezer) and William Ward (Bill).”

Henry’s Blueshouse and The Crown would go on to become fertile breeding ground for not just Black Sabbath but many gargantuan names in rock, with future stars like Robert Plant (who played with several of his bands before he formed Led Zeppelin), John Bonham (Band of Joy and a fellow Led Zeppelin member), and Dave Pegg (Fairpoint Convention, Jethro Tull) also appearing in the members’ log book. The night played host to Thin Lizzy, Rainbow, Status Quo, and Judas Priest as well. But it was the boys from Aston who would find their fortunes bound up with that of Henry’s founder.

Harsh sound, harsh surroundings

To this day, Aston is a working-class area with rows of unassuming two-up, two-down terraced houses — although it was properly easier to find a parking spot back in the days when the boys of Black Sabbath were pounding the streets.

“I can’t think of any other intersection in the UK or perhaps even the world where members of a band as successful as Black Sabbath would grow up in such close proximity to each other,” says Jez Collins, founder and director of the Birmingham Music Archive (and self-proclaimed Sabbath superfan), as we turn onto Whitehead Road.

The road is a nucleus, connecting the surrounding sprawl which shaped the band in their early years. Tony attended Holte Grammar School on Whitehead; Ozzy was a pupil at Prince Albert Junior School; both of them later went to Birchfield Road Secondary. Bill grew up slightly further away, the other side of Villa Park, while Geezer was raised on nearby Victoria Road.

“At one end you had Aston Hall and Aston Villa’s Villa Park,” points Collins, “at the other you had Birchfield Road, not far from Newtown Leisure Centre and the Barton Arms pub where they would later rehearse their debut album and go for pints.”

While “much has changed,” in the 60-odd years since the band lived here, Collins says key Sabbath touchstones remain, “like the original Holte Grammar School, the fire station and the Sacred Heart Church”. We’re now walking past the latter on the way to Ozzy’s childhood home, on Lodge Road.

“What’s interesting about Sacred Heart,” muses Collins, “is although the band claims to have not been influenced by religion or black magic, there are dozens of crucifixes inscribed into its bricks. Ozzy in particular would have walked past this broody church every day on his route from his house to his school, Birchfield Secondary. It could be that such imagery subconsciously crept into their thinking.”

If the area left such deep marks on Ozzy, he returned the favour; look closely at a brick to the left of the white UPVC front door to 14 Lodge Road — his former home — and you’ll spot the words ‘Iron Void’ carved into it, something Ozzy did as a teen when he was thinking of band names.

"It was at this front door where fellow local musicians, like Geezer first knocked on for Ozzy, answering an ad for band members Osborne had placed in shop windows. In Ozzy’s 2009 autobiography, I am Ozzy, he says the ad read: “OZZY ZIG NEEDS GIG” in felt-tip capital letters. Underneath he’d written: “Experienced front man, owns own PA system, 14 Lodge Road” and that he could be reached there between 6pm and 9pm on weeknights.

It’s partially true — at that point Ozzy did own a PA system, purchased from George Clay’s music shop next to the famous Rum Runner nightclub on Broad Street — but he was not an experienced front man, and like most people in post-war Aston, didn’t have much to his name.

Almost every family home in Aston housed local factory workers. Ozzy’s father, John, worked nights as a toolmaker at the General Electric Company (GEC) on Electric Avenue. GEC was a major player in Aston, employing up to 18,000 people at its height. While the business didn’t directly manufacture planes and weapons for use in war like other nearby factories, it did produce radios and the lamps used in searchlights by the British army. This drew attention to Aston during World War II, with the Luftwaffe bombing the area on many occasions during the Blitz, between August 1940 and April 1943.

But two decades later, two young men were more concerned with the latest fashions than bomb damage. In his book, Ozzy recounts the great amusement he experienced clocking Geezer’s velvet trousers for the first time, describing him as having “long hair and a moustache” and looking like a “cross between Guy Fawkes and Jesus of Nazareth”. Despite differences in sartorial tastes, Ozzy joined Geezer’s then-band Rare Breed for a short lived “one-gig career” (that’s all Ozzy can remember, unsurprisingly) before they called it a day.

Ozzy’s ad was still paying dividends though; it summoned both Tony and Bill to also turn up at his door, although Tony was initially reluctant. He was in the year above Ozzy at Birchfield Road and called him the “school clown”. Eventually, he gave in and Earth was formed.

Tony’s inimitable guitar playing style is ascribed to an accident he suffered while working at a metal sheet metal factory in Aston at the age of 17. On his final day of working there, Tony was moved to an unfamiliar workstation and ended up slicing off the tips of his middle and ring fingers of his guitar-playing hand. He was told he would never be able to play guitar again. Such was Tony’s ingenuity, he made thimbles from a melted down Fairy Liquid bottle and welded them to his severed fingers with a hot soldering iron, moulding them into fingertip shapes. This created a more abrasive guitar sound which nobody has ever been able to mimic. Nothing is more metal than that.

Coming of age in 1960s Aston was not for the faint-hearted, and Ozzy, Tony, Geezer and Bill witnessed such post-war devastation first-hand. In I am Ozzy, Ozzy mentions the “bomb building sites,” around Lodge Road that he used to play on as a child. “For years,” he remembers, “I thought that’s what playgrounds were called.”

Big break

It seems obvious that such harsh industrial surroundings might result in a similar soundscape. Jim Simpson has previously acknowledged this; in other interviews he says the music “reflected our industrial background”. US promo used to read 'Black Sabbath — music from the industrial heartland of Birmingham UK'. But speaking to me, he cites another reason that led Earth from blues to heavy metal in those early days: time constraints.

After 13 July 1968 — the date of their first official performance at Henry’s Blueshouse —, Earth was firmly on Simpson’s radar; a small regular slot quickly saw them turn into the main act, attracting audiences exceeding the 160 room capacity. “I’m sure on some of those nights we had well over 200 in,” Simpson says. Eventually, Sabbath asked Simpson to manage them. He was thrilled.

Earth were in demand but their sets weren’t long, requiring them to cram a lot of material into a short amount of time. Simpson attributes the creation of the harsher sound that would be coined as ‘heavy metal’ to the fast-paced nature of gigging. “The music just naturally got faster, and it matched the new name”.

As for that name, Simpson takes a bit of credit.

“I personally thought the band name Earth was too passive, it sounded like a quick fart,” he chuckles. “We would have official meetings at my home in Edgbaston and at one in 1969 I told them that they needed to change their name to something more authoritative, or harsher sounding.

After a bit of back-and-forth, Geezer poked his head around the door. “I’ve got it,” he exclaimed! “Black Sabbath”. He took the name from the title of a 1963 Italian horror film directed by Mario Bava.

“This was the first time we’d agreed on anything,” says Simpson. “The rest is history.”

The band’s first gig as Black Sabbath was, naturally, at Henry’s Blueshouse, on 17 October1969. It was the same day the band had finished recording their self-titled debut album (platinum or gold in almost every country across the globe at the time of writing). They soon outgrew The Crown and moved on to slightly bigger venues like Mothers, an Erdington venue voted the best rock club in the world by America’s Billboard magazine for two years running (1969 & 1970); and the Odeon on New Street.

“Eventually they filled every room in Birmingham,” Simpson adds, pointing out that it was at this point Sabbath started to get noticed by record labels and publishers in London, then further afield in the U.S. “By the end of 1970 they were wooed so much by the posh hotels, chauffeurs and lifestyle that London record labels and band managers would offer them, [they] were eventually convinced to move on,” Simpson reflects. He doesn’t mention it to me, but reportedly, the band let him go that year, via a surprise letter from their lawyers, coldly telling Simpson not to contact them again.

He couldn’t have been doing too badly though: Black Sabbath’s first two albums are arguably their most critically acclaimed, and their most popular song, ‘Paranoid’, was released under his stewardship. Despite the brutal parting of ways, Simpson’s affection for all things Sabbath shines through, especially for their fans. He says his Sabbath archive — including every single newspaper cutting from his time as their manager — has been collected with them in mind. He’d like to create a public display but doing so would take “about six months [and] some level of arts funding”.

After 1970, Sabbath left Birmingham to pursue global fame. Some set up bases in the Home Counties, others — notoriously — in L.A. But they’re finally back in Brum this year, to play one key venue they’ve yet to grace in nearly six decades of making music: Villa Park, their home stadium.

They’ll be there on 5 July 2025 for one huge final homecoming show, joined by the likes of Metallica, Slayer, Pantera and other globally renowned bands inspired by these four lads from Aston.

Simpson doesn’t know whether he’ll be joining them though.

“It’s great that they’re coming back, but I haven’t been invited… yet,” he says, a little sadly. “I saw some tickets were on sale for upwards of £600. I’m not sure how to feel about it all.”

Comments