Antonia Listrat almost didn’t make it to university. As a member of the country’s ‘Covid cohort’ — pupils who finished secondary school in 2020 — her A Level results were decided for her, based on the average results achieved by former pupils where she lived. For a bright young woman who wanted to be the first member of her family to get a degree, this outcome was gut-wrenching. “I lived in a very poor area,” she says of her upbringing in Essex. The average grade there was D-, so Antonia was awarded Ds and was unable to get a place. Undeterred, she home schooled herself for a year, then sat the exams. Happily, she was offered a place to study International Law and Globalisation at the University of Birmingham (UoB) and moved here in the autumn of 2021.

Antonia, now 22 and in her final year, is a softspoken humanitarian — the kind of person who feels other people’s struggles very deeply. “I find it hard in society when things are so unjust and unfair and I have a lot of empathy with people,” she tells me. It isn’t too surprising, then, that on becoming a student, she also became an active human rights campaigner. One project she took part in sought to improve youth provision in deprived areas, another to defend the rights of Travellers.

However, it was the seismic shift in Israel’s decades long occupation of Palestinian territories after Hamas killed 1,200 people in Israel on 7 October 2023 — prompting Israel's campaign of devastation in Gaza, which the International Criminal Court of Justice has said involves human rights violations suggestive of genocide — that shifted Antonia’s focus to the UoB itself. Specifically, she and likeminded students took issue with the uni’s relationships with weapons suppliers and arms manufacturers, like BAE Systems, whose products are used against innocent Palestinians. Why is it, she thought, that a place of learning should have, directly or indirectly, significant investments in and partnerships with companies that allegedly have ties to Israel and its documented war crimes?

Cut to today: Following a win in court for the UoB, Antonia and another student, 20-year-old Mariyah Ali, are facing disciplinary procedures which could result in their expulsion and stop them from graduating. Their cases are unfolding in the midst of a debate between the UoB and the Birmingham University College Union (BUCU) about The University’s Code of Practice on Freedom of Speech, with BUCU concerned that the amended code is both burdensome for staff and too vague. It’s a combination they argue hands power to university bureaucrats to decide what does and does not constitute free speech. The UoB, on the other hand, insists the Code underpins its commitment to freedom of expression.

Back to October 2023: as it happens, Antonia began studying a module on transitional justice after genocide. Over the next few months, the connection to what she was learning in lectures and what Israel was doing in Gaza became clear to her. “While we were watching a genocide live on our screens, the module was discussing past genocides and how people tend to deny that they are happening,” she says. She felt compelled to speak out.

‘This is what a university should be’

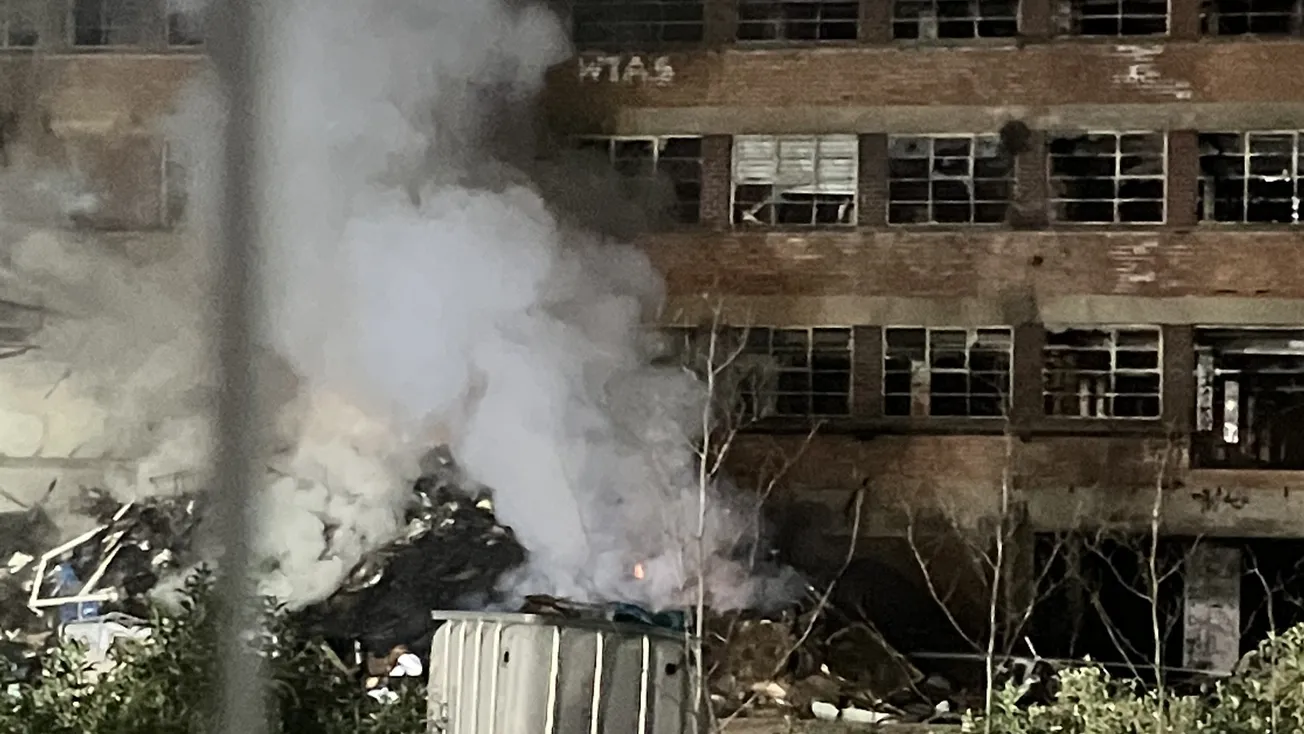

In early May, inspired by students at American universities like Columbia, who had established protest camps to try to pressure their institutions to divest from companies that resource Israel’s armed forces, Antonia, Mariyah and their peers pitched up their tents. First, a camp appeared on the large patch of grass in front of the library called the Green Heart, then in Chancellor’s Court outside the stately Aston Webb Building. They called themselves the Birmingham Liberated Zone, and while it was mostly students who were camped out, the broader coalition of about 1,200 included — and still includes — staff members and faculty.

From the Zone’s perspective, the camp was exhilarating. “It was the best thing we did; the campus was alive,” says Antonia. Fellow students and members of the public visited, bringing hot meals. Family days were organised where children painted and crocheted; lecturers came down to provide political education. Ellen Shobrook, who is a careers educator and president of BUCU, and who has worked at the UoB for 17 years, tells me: “It was the first time it felt like this is what a university should be, with organic conversations about important issues and proper community engagement.” Interestingly, documents from a later court hearing include reference to campus security logs from that time which were presented as evidence. The judge writes that they “mostly showed regular prayer meetings and peaceful, welcoming protests”.

Not so for the university’s senior management team. They were unhappy that university land had been occupied and that the camp was causing disruption. They were also concerned about the safety of students and staff — the UoB’s Head of Security, Mark Lawrence, told the court he personally found a group of 20 or 30 students intimidating when he sought to persuade them to take down a banner. Several attempts by management to meet with the Zone members and convince them to pack up and leave failed because the Zone were unhappy with the terms proposed. They wanted to meet with Vice Chancellor Adam Tickell and to be able to discuss their demands, to cover their faces and have a guarantee that their negotiators would not face disciplinary action.

On 11 June 2024, in one of his regular email updates to the student body, Tickell painted a very different picture of life on campus since the camp appeared. He explained that he would not tolerate the protesters hiding their identities with masks, or their inviting external groups and speakers to campus without permission. He also accused them of shouting at and intimidating staff members and of spraying paint and graffiti on historic buildings and university entrances.

The Zone refutes these latter charges — protest is loud by nature, they say, and they have the right to do it. They strongly reject any accusation of intimidating behaviour. The spray paint was the work of a separate protest group, Palestine Action. Nevertheless, Tickell had made his decision, “with a heavy heart”, to seek a Possession Order for the camp’s removal. In early July, the UoB took Mariyah Ali — the only student named on the defence — and the rest of her cohort to court, armed with a 500 page dossier of evidence. A week later, the judge ruled in the UoB’s favour. Court bailiffs arrived at five in the morning to evict the camping students.

Unsurprisingly, the Zone was unimpressed with the evidence used against them, in particular a staff complaint regarding an event which took place on 4 June at the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences. The complainant describes the students marching towards the building while wearing “balaclavas”, which the writer claims is traumatic for people with lived experience of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, domestic violence and other global conflicts. What actually happened that day was that a group of three Zone members, accompanied by two representatives from the union UNISON, had attempted to deliver a letter of their demands to Tickell who was speaking at the event. Antonia says they weren’t wearing balaclavas — they had on keffiyehs and surgical masks — and I verified this with both UNISON reps. “It is very strange that a symbol of Palestinian solidarity was associated with domestic violence and The Troubles in Northern Ireland,” says Antonia. The UoB did not respond to my specific questions about the balaclava claim but reasserted its commitment to free speech.

Crackdown on campus

Prior to all this, the university had been busy, quietly updating its Code of Practice on Freedom of Speech. The updates were partly required to line up with new legislation and were informed by expert legal advice. The Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023 was the former-Conservative government’s response to what it perceived as the growing issue of ‘cancel culture’ at UK universities, and it was due to come into force on 1 August 2024. The UoB completed a review of its code in April, before government guidelines were due for release in mid-August. Regardless, after its election in July, the new Labour government decided to pause the Act’s implementation, due to their concerns that the statute would potentially place a legal requirement on universities to give a platform to extremist speakers. The Dispatch understands the code has been updated since this development but BUCU says this amounts to a minor reference to the pause.

Concern about freedom of speech on campuses, of course, isn’t limited to Birmingham or even the United Kingdom. In November, in a report to the United Nations, Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, Gina Romero, said she is “deeply concerned" about the vilification of peaceful solidarity protests organised by students globally “and universities’ ties with companies alleged to be involved in war crimes.”

BUCU objects to the Code changes and to the fact that unions were not consulted on them before they were agreed (The Dispatch understands that universities have no legal obligation to do this but that it is not uncommon). “In our view, the code is legally problematic,” Ellen Shobrook tells me. The central issue, as BUCU sees it, is that the guidance is incredibly bureaucratic, to the point it is “potentially unworkable in its current format”. They worry, that without clear guidance, the administration will have the power to pick and choose which events and speakers they deem acceptable.

All of this is relevant to the Liberation Zone because the code was cited in the UoB’s court case against them. The judge remarked that the Code of Practice was evidence that the university was acting fairly. It has also enabled the UoB to bring disciplinary procedures against Mariyah and Antonia, for their potential part in unauthorised protest and protest-related activities on campus. University librarian and UNISON branch secretary Mike Moore thinks the changes to the Code of Practice make it easier to discipline students because it broadens the scope of provisions required for protests to be approved. Moreover, that they dilute the impact of protest which is necessarily disruptive and occasionally spontaneous. Think about it, if the only form of protest which is sanctioned is the kind which is pre-emptively scrutinised by the authorities, it isn’t going to be very effective — which is the very point of demonstrating.

Mariyah was summoned to a disciplinary hearing in June for a protest that was held outside a meeting of the UoB’s investments sub committee in May. It is referred to in the documents from the court hearing — the UoB gave evidence that staff were “visibly shaken” when the students “shouted, chanted loudly and banged on doors”. Mariyah, however, disputes that she was in anyway disorderly or intimidating and that her basic right to protest a genocide has been eroded. “I continue to attend classes, work on my dissertation, and try to hold myself together, all while carrying the weight of uncertainty,” she says. Antonia is due to have her hearing this month regarding the same protest and two events the Zone held during the UoB’s September 2024 Welcome Week: a picnic and a meet and greet at which they erected tents on campus, both of which were crushed by security. She says she is feeling very low and has periods of anxiety, especially because, if she is unable to graduate, it will devastate her family.

The two women aren’t sure why they have been singled out for punishment, except that they are both very engaged and outspoken activists, especially since the Birmingham Liberated Zone began. “I just care a lot about the cause and the student movement, and I believe that the university management saw how passionate I am and wanted to make an example out of me,” says Antonia. Last week, the Zone launched a petition calling for an end to the disciplinaries.

The UoB would not comment on individual students, but a spokesperson told me that the university does not recognise the Zone and that it is not an affiliated student group. They said the UoB had “a very strong and longstanding commitment to freedom of speech and academic freedom” and that “the safety of all our students and staff is of paramount importance and we are committed to providing a safe, welcoming, and inclusive environment for all.”

We are yet to find out if that includes Mariyah and Antonia.

Correction: An earlier version of this article described the relationship between Israel and Palestine as a conflict. We have changed this to the more accurate description: occupation of Palestinian territories.

Comments