In the popular imagination, Birmingham isn’t thought of as an artistic bohemia. The city’s historic stereotype, judging by the backdrop to the likes of Peaky Blinders or the risible Tolkien biopic from 2019, is summed up by no-nonsense men bashing iron in huge factories, often to a heavy metal soundtrack.

This imagery is a projection of the city’s more working-class 20th-century social structures onto a more complex past. In the 19th Century, Birmingham’s main industries were skilled and artisan: jewellery, decorative metalwork, pen nibs, and later, machine tools and engineering parts, explaining why Birmingham, contrary to all the stereotypes, had quite an early interest and education in the visual arts. (Albeit, an interest that was mingled with its need to support the crafts on which prosperity was based.)

This legacy is visible in Birmingham’s buildings today. To those who claim that the city has little that is truly distinctive, I would point to the remarkable Arts and Crafts architecture in the streets behind Colmore Row, including the Midland Institute and the School of Art. These structures distil the city’s history: a combination of artistic pedigree and municipal gospel — something uniquely and gloriously Brummie.

I would also point to Birmingham’s coat of arms, designed during a late Victorian peak. Sure, it features a burly blacksmith; but on the other side of the shield is a female figure holding a painter’s palette; art meeting industry. It was understood that Birmingham was not just an industrial city: its wealth was built on the back of a combination of aesthetics and manufacturing.

To understand how this came about, we need to go back to the mid-1700s — the time of the Midlands Enlightenment and the Lunar Society. This period saw the establishment of schools teaching the basics of drawing and painting — essential for the production of the decorative pieces for which Birmingham was increasingly known. The most famous, on Great Hampton Street, was run by Joseph Barber, a Geordie who moved south to work in the city’s flourishing japanning trade — a type of lacquering that attempted to copy East Asian styles. Another important figure is Stroud-born David Bond, who also worked in japanning before managing the ornamental side of the Soho Manufactory for Matthew Boulton. Many of his landscapes were exhibited in London, but he also trained artists.

Barber and Bond began the loosely knit ‘Birmingham School’ of landscape painting, united by a progressive style compared to other landscapists — think proto-impressionism. A prominent member, David Cox, was born in Deritend to a blacksmith and trained at Barber’s school. He would go on to become one of the most celebrated landscape artists of the first half of the 19th Century.

Many of these artists, emerging out of the crafts of the city, often continued to work on manufactured items and for entrepreneurs: alongside their more artistic outputs. While this explains some snobbery the group experienced in London, it also supports the imagery on Birmingham’s coat of arms; the union between art and commerce that began in the 1700s became a key strain in our history.

Importantly, Barber’s sons and one of his pupils set up another school, dedicated to life drawing, on what is now the site of New Street Station. What became the Birmingham Society of Arts eventually split; one half kept the moniker, receiving royal patronage in 1868; it still exists with its HQ and gallery in the Jewellery Quarter. The other half — a result of business-minded patrons wanting more of a focus on the commercial aspects of art and design — became the Birmingham Government School of Art. This was taken over by the council, becoming Britain’s first municipal school of art — and, at its time, perhaps the most progressive institution of its kind in the country.

By this time, the cultural context had changed. Horrified by industrialism and mass production, critics such as John Ruskin had — completely fancifully — looked back to the Middle Ages: a time when individual creativity and craftsmanship were, supposedly, at a peak. Victorian radicals, as demonstrated in the excellent recent exhibition at Gas Hall, combined reforming social ideas with a backwards-looking worldview: ignoring the dirt, disease, violence, poverty and ignorance of medieval times.

Ruskin’s fellow-traveller, the architect Augustus Pugin, rejecting the ‘dishonest’ classical forms preferred by the Georgians and earliest Victorians, called for a return to the values of the medieval Gothic. He initially hated Birmingham, “that most detestable of detestable places… where Greek buildings and smoking chimneys, Radicals and Dissenters are blended together.” But after his conversion, he would teach architecture at the Catholic Oscott College in Sutton Coldfield and design several buildings in the city.

The Gothic revival created some impressive churches in Birmingham — as well as Pugin’s masterwork, St Chad’s, and its Bishops’ House, lost to Herbert Manzoni’s ring road — but its mid-Victorian heyday has left less of a mark in the form of grand industrial and commercial buildings than in some other city centres. This is because, during Birmingham’s heyday during the middle years of the 1800s, the city had a penny-pinching council which abhorred large-scale civic projects. But also because the largest buildings, such as Mason College on Chamberlain Square and the Exchange Buildings next to New Street Station, have been demolished. The grandest survivors face each other at the neglected end of Corporation Street: the Victoria Law Courts and the Methodist Central Hall.

Mostly, Birmingham’s house style would remain an elegant, if understated, classicism typified by the Victorian library and institute (demolished in the 1960s for the ring road) or Yeoville Thomason’s buildings: the Council House, Singer’s Hill Synagogue, or the Union Club on Colmore Row. But the new medievalism impacted the city’s built form indirectly, through the strength of its arts and design traditions. The prime mover was Edward Burne-Jones. Born to a frame-maker living on the site of what is now the Briar Rose pub on Bennett’s Hill, he attended King Edward’s School in its original site on New Street (another of Birmingham’s vanished neo-Gothic buildings, with interiors by none other than Augustus Pugin).

At Oxford, alongside fellow Brummie Charles Faulkner, he became a member of the ‘Birmingham set’ (later ‘the Brotherhood’) with the radical thinker William Morris. This association also marked, in some ways, the birth of the Arts and Crafts movement — while later shaping the architecture of Birmingham. The set was brought together by literature and poetry, but their interests extended to art and social reform. William Morris, who partly bankrolled the gang through his family wealth, became linked with the city.

Morris became the first president of the newly municipalised school of art, with Burne-Jones and fellow pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais among his successors. (Burne-Jones, meanwhile, became a painter and gave Birmingham perhaps its most celebrated piece of public art, the stained-glass window in St Philip’s Cathedral.)

Birmingham’s world-beating collection of pre-Raphaelite work can also be traced back to this period when the London-based Magazine of Art called it “the most artistic town in England.” As Dr Serena Trowbridge at Birmingham City University, an expert in the movement, explains: “Because the city was training so many people, there was a strong sense that it was important to have a collection of the finest work that they could find.”

The School of Art, unsurprisingly, became a centre for the pre-Raphaelite movement as it evolved into the Arts and Crafts. Spearheaded by Morris, Arts & Crafts shared the medievalism of the Gothic revival, while emphasising a more homespun, rural style; a ‘folk revival’ for architecture and the decorative arts.

Women, although often treated as muses rather than artists, did have a relatively high profile in both movements. Birmingham-born Kate Bunce — the daughter of an editor of the Birmingham Post: studied at the School of Art which, unusually for the time, allowed women to enrol as students. Her paintings are in several Birmingham churches, typically alongside metalwork by her sister Myra.

Meanwhile, after his death, Morris’s daughter May taught embroidery and jewellery at the school. Alongside her students, she helped to revive these crafts, which were treated at the school as equal to painting or sculpture. She later founded the Women’s Guild of Arts. Indeed, some of Morris' designs have been revealed as her work rather than her father’s, prompting wider questions about the extent to which women’s work sits behind the men who dominate this piece.

One local, early, disciple was the architect John Henry Chamberlain (no relation to Joseph). He began as a follower of Pugin, but the rising influence of the Arts and Crafts movement is apparent in many of the board schools he designed with his partner, William Martin. This is most obvious at Oozels Street School, now the Ikon Gallery. But his masterpiece is the School of Art itself, a building that sits on the boundary between the Gothic Revival and Arts and Crafts.

Arts and Crafts architecture is found in plenty of places, of course. So, what makes it uniquely Brummie? Well, it was mostly a rural and suburban aesthetic — as it is in parts of this city, too. There are plenty of churches and detached houses designed by Chamberlain as well as another arts and crafts devotee, Wolverhampton-born William Bidlake, who would pioneer architecture teaching at the School of Art. Morris himself was, after all, not a devotee of any sort of civic gospel; indeed, he was explicitly anti-urban. As with many thinkers of the period, he combined radical social ideas with a hatred of cities and a desire to return to the land and an idealised village society.

Chamberlain was a devotee of Ruskin and Morris, but he was also one of the close-knit group around his namesake Joseph Chamberlain and the preacher George Dawson. Dawson’s ‘civic gospel’ emphasised the city as the home of everything related to progress. While Morris wanted to get rid of cities, Birmingham’s elite wanted to humanise them.

Chamberlain’s attempt to reconcile these conflicting ideologies, together with the influence of the School of Art, explains why Arts and Crafts became an urban form in Birmingham. On Cornwall Street, Edmund Street, Newhall Street and Church Street, in an area now prosaically named the Colmore Business District, a clutch of buildings manages to feel both grand and deeply grounded in the Arts and Crafts aesthetic. The finest example stands on Colmore Row: the grade 1 listed Eagle Insurance Building, now the Java Coffee Lounge, designed by William Lethaby and described by the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner as “one of the most original buildings of its date in England.” There are a few other clusters, notably in the Jewellery Quarter, although many were lost to post-war rebuilding, notably around the High Street.

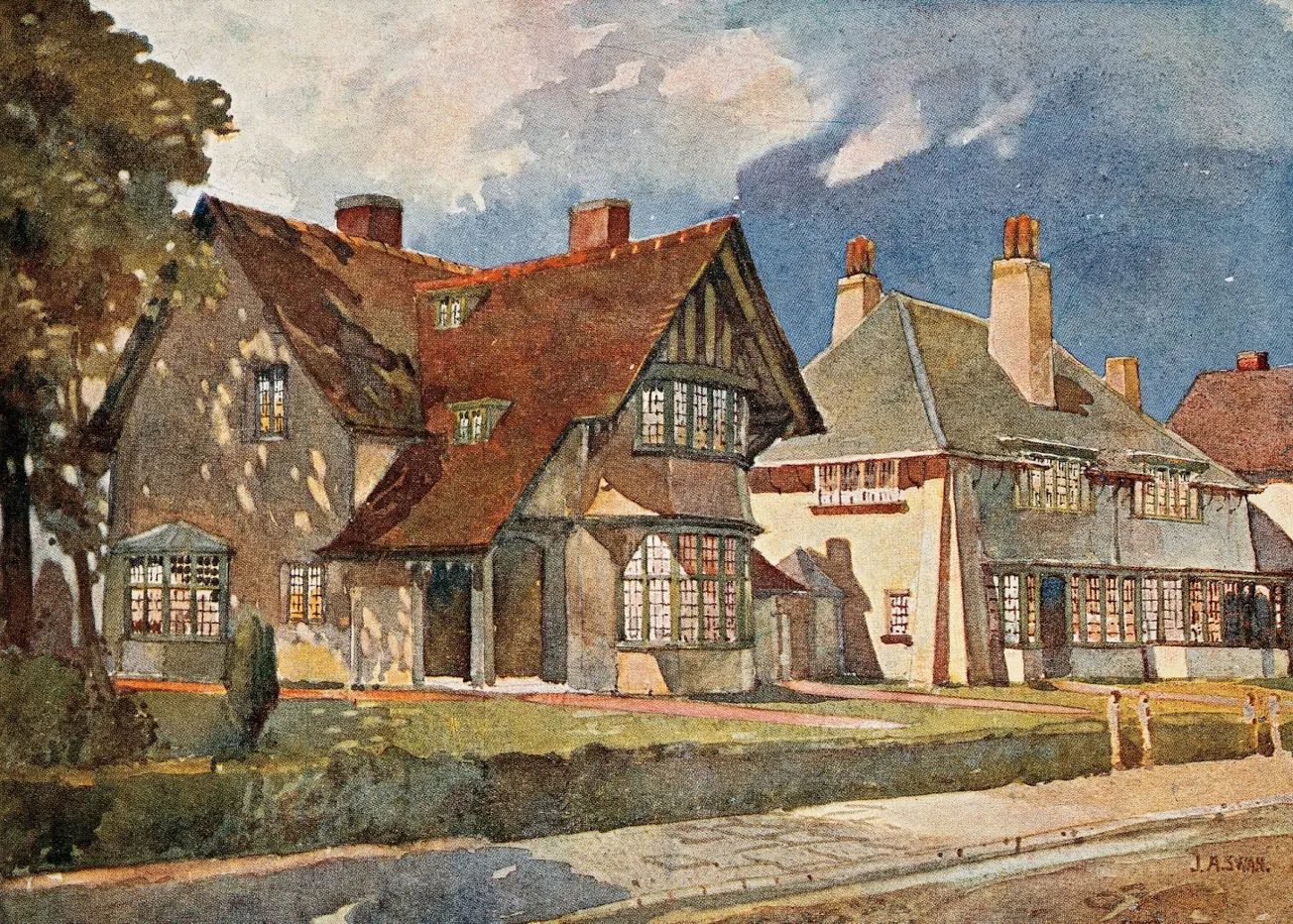

A very different route was taken by a student at the School of Art, aspiring architect William Harvey. At a young age, he was selected by George Cadbury to design the first streets and houses at his model village in the Worcestershire countryside, which he would name Bournville. Here the Arts and Crafts influence is conventional and folksy, conveying a rural idyll. As lovely as Bournville is, there’s nothing urban about it; it might be in the city now, but its roots turn their back on the metropolis. Its influence can be felt, albeit indirectly, in the vast wave of suburbanisation occurring in Birmingham during the early 20th Century.

This suburbanisation happened elsewhere, but in Birmingham, it was deliberately encouraged by Quaker and Unitarian reformers keen to replace rather suspect terraced houses, pubs, music halls and grand Victorian edifices. In their place, these non-conformists would prescribe cottagey houses, folk dancing and copious quantities of gardening. By the 1930s, a sort of debased Arts and Crafts design had become widespread in the form of a huge ring of semi-detached, Tudor-inflected housing; the original aesthetics, once radical, had become the height of ordinariness and respectability. This applied in Birmingham’s art world too; the surrealist movement in the city railed against the conservatism of its once-progressive art establishment from the house of its eccentric leader, Conroy Maddox, in the more urban environs of Balsall Heath.

Birmingham often feels like a city wanting to escape from itself — building more Bournvilles. It doesn’t help that its elite residential district, Edgbaston, is mostly a low-density suburb (despite its age and inner-city location.) Bristol’s Clifton, the nearest point of comparison, is a very different place, composed largely of dense and tall terraces. In Edgbaston, this kind of urbanism only exists in the streets nearest to the city centre.

Birmingham does, occasionally, offer glimpses of an alternative version of itself — Edgbaston’s art deco flats, or the streets of the Jewellery Quarter. The buildings off Colmore Row are another; they’re just a fragment of the city centre; but they show what the city might have been like had it not taken a wrong turn later in the 20th century. It might have had a more unified look and feel, or become a national architectural trendsetter. But most of all, these buildings speak to the city’s history: tensions between urban ideals and rural longing, and the attempt to bring together commerce and art.

Comments